Next to images of world-class museums, the works of Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams are some of the most ubiquitous adornments of mouse pads, novelty mugs, reception rooms, and coffee tables. Finding their way into the mundane trappings of our daily lives and spawning countless imitators, Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams's imagery permeates the American cultural consciousness. SFMOMA's summer exhibition, Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams: Natural Affinities, brings together the visions of two illustrious twentieth century artists by showcasing their respective explorations in Taos, New Mexico where O'Keeffe and Adams first met in 1929. Responding to the unique natural landscape, vast skies, and cultural history inscribed in its landscape and structures, the artists capture the mythic beauty and enigmatic anima of the region.

Despite the consumerist popularity of this exhibition, this show remarkably avoids trite predictability, the pitfall of exhibitions featuring widely popular artists. Indeed, the exhibition's strength lies in its ingenious pairing: the dialogue between O'Keeffe and Adams's imagery, painting, and photography; their respective interior visions and exterior surroundings; and their use of vivid color and sensuous monotones all effectively energize the show with dynamic dialogue. Most significantly, this dialogue refutes the tendency to view their works as passive, decorative images: O'Keeffe's natural abstractions emanate distinct palpability when viewed in the flesh—her visible brushstrokes have a presence distinct from the clean, flat, watery look of her reproductions. Likewise, Adams's photographs have an astonishing depth and sumptuousness when viewed in their original format—though the reproduction in Adams's books are notably of very high quality.

One cannot help but perceive a distinct competitive streak amidst the exchange between Adams and O'Keeffe's visions in this exhibition. Indeed their personalities, constructed and immortalized in autobiographies, were in opposition to one another: O'Keeffe was known for her guarded, laconic conceit and Adams for his effusive public charisma and ingenuous enthusiasm. Adams and O'Keeffe were in different places in their careers upon their initial meeting in 1929—O'Keeffe, more than a decade Adams's senior, was already enjoying a successful career; whereas Adams was still just a promising newcomer. The ostensible compatibility of Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams's work belies the changeable nature of their long-lasting acquaintance, which, according to Richard B. Woodward's essay in the accompanying catalog, grew rather tenuous at times. It's safe to say however, discerning whose work surpasses whom, or whose work is more indebted to whom is beside the point—indeed, such thinking limits the interpretive potential of this exhibition and does not permit one to go further after arriving at a conclusion. It is thus more fruitful to approach this exhibition as a way to experience the richness of their work when viewed together.

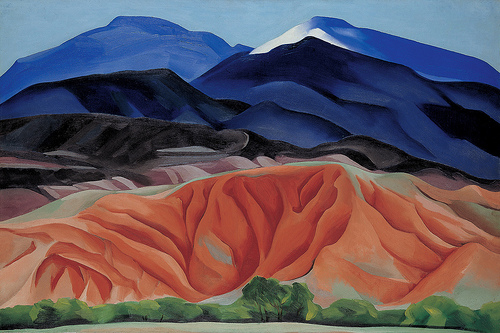

One witnesses the pair's striking affinity in Ansel Adams's Winter Sunrise, The Sierra Nevada from Lone Pine, California (1944) and O'Keeffe's Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico/Out Back of Marie's II, (1930). Though these images depict landmasses in different locations and were produced nearly fifteen years apart, the composition and dramatic chiaroscuro of the mountain ridges draw strong parallels. Adams's photograph explores the varying textures and sensual qualities of the landscape's surface, pronouncing these differences by utilizing a high contrast light pattern—evidenced in the jagged contours of the white mountain in the background—to the soft, placid slope of the darkened hill in the foreground. O'Keeffe adopts a similar device to articulate texture and mood by contrasting warm and cool hues. As the eye moves around her painting, one senses the cool, calm loneliness of the blue-black mesa; the warm, dry environment of the grooved, orange landform; and the verdant ease of the greenery at the mountain's base.

O'Keeffe and Adams's work in New Mexico, however, produce the most compelling dialogues—a body of work where both artists produced pieces of singular vision that do not necessarily adhere to the conventions of the rest of their respective portfolios. In Ansel Adams's, Saint Francis Church, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico, (1929), the structure appears to rise organically out of the humble elements of the desert, drawing parallels between the sacred purpose of the building with the natural sublimity of its appearance. While this image retains the sharp detail and pronounced contours of his landscapes, the close framing calls attention to the geometry of the subject, imbuing this photograph with an abstract impression that evokes the compositional challenges of abstract painting. By using his camera to an expressive end, as evidenced in this decidedly atypical and enigmatic photograph, Adams compels viewers to recognize the artistic capabilities of the photographic medium. O'Keeffe's treatment of the same subject in her painting, Ranchos Church No.1, (1929) expresses a similar connection between land and spiritual structure as well as a similar composition, in which the church occupies most of the compositional space.

Though there are tangible and obvious differences between Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams in terms of age, treatment of subject, personality, and chosen medium, their works, when viewed together, produce a dynamic dialogue akin to a musical harmony of two distinct yet compatible bodies of work. Indeed, their similarities are remarkable as well: historians and critics hail both artists' works as definitively "American," and credit them in part with bringing American culture out of Europe's shadow. Their high visibility and widespread esteem have bestowed their work with enduring associations: one can hardly think of the Southwest without envisioning O'Keeffe; likewise, Adams's work has become synonymous with the American wilderness and environmental advocacy. Furthermore, both O'Keeffe and Adams have become icons in the popular imagination—they are famous as much for their distinct, and consciously cultivated public personae as they are for their unique styles. There is much to discover and engage with in this uniquely dialectic exhibition of two significant visual artists.